Saint John - Chapter 5

|

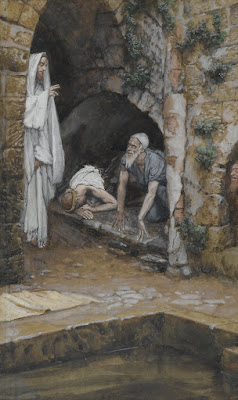

| Piscina Probatica. J-J Tissot. |

After these things was a festival day of the Jews, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem.

After these things, &c. Observe, John here omits many things which Christ did in Galilee, but which Matthew records from the 4th to the 12th chapter of his Gospel. For what Matthew relates in his 12th chapter concerning the disciples plucking the ears of corn took place after the following feast, as will appear presently.

A festival. SS. Chrysostom, Cyril, and others think that this was the Feast of Pentecost. With more probability, S. Irenæus (lib. 2, c. 39), Ruperti, and others, think it was the Passover. They show this (1.) Because in chap. 4 ver. 35, Jesus said there were still four months unto harvest. That therefore must have been before the Passover: thus the Passover must have been the first great subsequent feast.

2. Because the Passover was the feast of feasts. When therefore it is said absolutely, there was a feast, the Passover, which was the feast par excellence, is to be understood.

[NB: The Passover begins on the 15th day of the month of Nisan, which typically falls in March or April of the Gregorian calendar. The 15th day begins in the evening, after the 14th day, and the seder meal is eaten that evening. Passover is a spring festival, so the 15th day of Nisan typically begins on the night of a full moon after the northern vernal equinox. However, due to leap months falling after the vernal equinox, Passover sometimes starts on the second full moon after vernal equinox. In 2019, the dates were 19-27 April. To ensure that Passover did not start before spring, the tradition in ancient Israel held that the first day of Nisan would not start until the barley was ripe]

3. Because Christ after His baptism preached for three years and a half, [see special post on ''A time and times and half a time'', published 17 November 2019] according to the common consent of divines. It follows from this that there ought to be notices in the Gospels of four Passovers, which is the case. The first is mentioned by John in 2:13; the second in this place; the third in 6:4; the fourth, just before His death, 19:14. But if the feast mentioned in this 5th chapter were not the Passover, we could only gather the mention of three by S. John.

Here then comes to a close the account of the first year and three months of Christ’s ministry, that is to say, from January 6, when He was baptized, until this second Passover, which was kept in Nisan, or March.

[2] Est autem Jerosolymis probatica piscina, quae cognominatur hebraice Bethsaida, quinque porticus habens.

Now there is at Jerusalem a pond, called Probatica, which in Hebrew is named Bethsaida, having five porches.

|

| Probatica, near Sheep Gate |

A pool: i.e., a place which contained fishes, or at least might have held them. The Greek is κολυμβήθρα, a place to swim in, because fishes, or even men, might swim in it. The Vulgate has piscina. This pool was constructed by Solomon for the service of the Temple; hence it is called by Josephus (Bell. Jud., vi. 6) Solomon’s Pool. In it the Nethinims washed the victims which they handed over to the priests to be offered in the Temple.

Some Greek codiees instead of pool read πύλη, a porch, or gate, but S. Chrysostom, Theophylact, Cyril, Euthymius, S. Jerome, and others passim, read κολυμβήθρα, i.e., a pool. The Syriac has a baptistery, or font.

Bethsaida: so read the Vulgate, and among the Greeks SS. Chrysostom and Cyril. And appositely, for Bethsaida means in Hebrew a house, i.e., a place of hunting, or fishing. And this is the signification of the Greek κολυμβήθρα, a place for fish to swim in. The Greek MSS., however, read Βηθεσδὰ: so also S. Jerome (loc. Hebrœis). Bethesda means in Hebrew a place of pouring forth, because the rain from the roofs of the houses, and streams of water from aqueducts, flowed into it. The Syriac has Bethchesda, or house of mercy, from the Hebrew חֶסֶד, chesed, mercy, because there God showed His mercy to the miserable sick whom He healed; or else because righteous men relieved with their alms the sick poor who lay there.

Having five porches, or porticoes: these porches or porticoes were places covered above, but open below, either for walking, or taking rest in, that sick persons might rest in them secure from rain, or the heat of the sun, and immediately step out of them into the pool when its angel moved the water.

[3] In his jacebat multitudo magna languentium, caecorum, claudorum, aridorum, exspectantium aquae motum.

In these lay a great multitude of sick, of blind, of lame, of withered; waiting for the moving of the water.

In them … languishing people (Vulg.); Greek, ἀσθενόντων; Eng. Ver. sick folk; withered (Vulg.) aridorum, dry, i.e., whose arm. or hand, or foot, or some other limb, was lifeless.

An angel of the Lord: either Raphael, or some other, Raphael, who presides over bodily healing, is so called from the Hebrew, which signifies the medicine, or physician of God. Whence he cured Tobit of his blindness.

[4] Angelus autem Domini descendebat secundum tempus in piscinam, et movebatur aqua. Et qui prior descendisset in piscinam post motionem aquae, sanus fiebat a quacumque detinebatur infirmitate.

And an angel of the Lord descended at certain times into the pond; and the water was moved. And he that went down first into the pond after the motion of the water, was made whole, of whatsoever infirmity he lay under.

According to a time (Vulg.), i.e., at a certain time determined by God, or the angel, but unknown to men. Wherefore what Tertullian and Cyril say does not seem to be correct, that it was only once in the year, namely, at Pentecost, that the angel went down into the pool. For if so, the sick folk would not have lain beside it (for so long a time), but would have waited at home until Pentecost was close at hand. As Euthymius says, “By speaking of a stated time, he showed that the miracle was not continually taking place, but at certain times, unknown indeed to men, though often, as I think, in the course of the year.”

The water was moved (Vulg.); Greek, ἐταράσσετο ὑδῶρ, i.e., he disturbed or troubled the water. “The sound of moving signified that angels were present to sanctify the water,” says S. Cyril. “The water was moved in order to show that the angel had descended,” says S. Ambrose.

And he that first went down, &c. In order to show the value of labour and diligence, and that we ought to be swift and active to take God’s benefits. Thus it was necessary for him who would gather the manna to rise at dawn, for when the sun was risen it melted, “that it might be made known unto all that it was needful to prevent the rising of the sun for Thy blessing, and to worship Thee at the dawning of the day” (Wisd. 16:28). For God gives His gifts to the watchful and earnest, not to the slow and sleepy. Thus in the race only he who excels the rest receives the prize (1 Cor. 9:24).

You will ask why, after the troubling of the water, as it is in the Greek, only he who first stepped in after the troubling was healed? I answer, that the literal reason was to show that this power of healing did not proceed from any natural virtue of the water, but from the moving of the angel, and the command of God. This moving of the angel did not impress any physical power or quality upon the water to heal any disease, but it was a sign of the Divine power and working, which were about to heal that sick person who had previously, by his own diligence, stirred up himself, and had gone down into the water that he might there receive the miraculous blessing of God. This moving, therefore, was an invitation to the sick to receive healing in the troubled water.

Appositely indeed did the angel make use of this sign of motion, because, whilst it was being moved, the virtue of the water became lively and efficacious. For life consists in motion, death in quietude and torpor.

Tropologically, the reason was to signify that the sinner, when he is converted and healed by God, is wont to be troubled and agitated in his conscience by various emotions of fear, shame, and hope. For by these God moves a man to repentance and contrition, that he may thereby be healed, as the Council of Trent teaches.

Of whatsoever disease. From hence it is plain that the healing virtue of this pool did not proceed from the victims which were washed in it, nor from wood lying at the bottom, of which the cross of Christ was afterwards made, as some have supposed, but was supernatural and miraculous. For God wished to bestow this benefit upon believing people about the time of Christ’s coming (for there is no mention of it in the Old Testament), in order that Christ thus healing a sick man might show that He was God, who had given this property to the pool, and therefore that He without it could heal the sick. Wherefore it would seem that this gift was taken away from the ungrateful Jews when they killed Christ, for we find no subsequent mention of it. As Tertullian says (cont. Jud., c. 13), “The pool of Bethsaida, which, to the coming of Christ, healed the sicknesses of Israel, afterwards ceased from bestowing its benefits through their persevering fury.”

Allegorically, God willed that this pool should be a token of His Passion and His Baptism. For as the angel descended into the water, so Christ went down to His Passion and torments; and in them, as in water, He was immersed and buried. And as the pool was red with the blood of the victims which were washed in it, so was Christ ruddy, and stained with His own blood (Isa. 63:2), that by the merit of His blood He might cause baptism (wherefore the Syriac here translates baptistery), in whose water believers are washed, to heal all spiritual infirmities. So Tertullian (de Baptismo, c. 5), S. Ambrose (de Spir. Sc., lib. I, c. 7), and S. Chrysostom. The latter says, “For when God wished to instruct us in the belief of baptism now nigh at hand, He drove away not only pollutions, but diseases by means of water: for the nearer the images and figures were to the truth, they were more illustrious than the ancient figures.” And S. Austin says, “To descend into the troubled water is humbly to believe in the Lord’s Passion. There one was healed to signify unity. Whosoever came afterwards was not healed, because whoso is outside of unity cannot be healed.”

|

| The man with an infirmity. J-J Tissot. |

And there was a certain man there, that had been eight and thirty years under his infirmity.

A man having an infirmity: Greek and Vulgate. S. Chrysostom and others say that this sick man was a paralytic.

Tropologically, this infirm man represents one who has grown old in a course of sin: who lies without strength in habits of vice, and is without any power to do good. For as palsy dissolves the bonds which knit the limbs together, so does a habit of sin enervate and dissolve the strength of the soul, so that men cannot arise out of it, and resist it, unless they are raised and strengthened by the mighty grace of God. Hence it is plain that such a palsy as this was naturally incurable; and we see that for thirty-eight years it could not be healed by any skill. Christ therefore took upon Himself to heal this palsy rather than the diseases of the other sick who were there, in order to show forth both His Almighty power and His infinite mercy. This was why Christ determined to heal Paul, who was labouring even beyond the rest of the incredulous and impious Jews under the worst spiritual disease of unbelief, as he himself shows us in the beginning of his 1st Epistle to Timothy. As S. Austin says, “The great Physician descended from heaven because one who was sick unto death lay on the earth.” On the symbolical meaning of the thirty-eight years see S. Augustine in loc., where he says, amongst other things, that it was the symbol of weakness, as forty is the symbol of healing and perfection. “If therefore,” he says, “the number forty has the perfection of the Law, and the Law is not fulfilled except by the twofold precept of charity, what wonder that he was sick, who lacked two of the forty?” The twofold love, viz., of God and his neighbour, was lacking.

[6] Hunc autem cum vidisset Jesus jacentem, et cognovisset quia jam multum tempus haberet, dicit ei : Vis sanus fieri?

Him when Jesus had seen lying, and knew that he had been now a long time, he saith to him: Wilt thou be made whole?

When Jesus saw, &c. Christ knew well that he had a desire to be healed, but He asked the question—1. To afford the sick man an opportunity for conversation, and from thence of being healed. As S. Cyril says, “Herein was a great proof of the compassion of Christ, that He did not (always) wait for the entreaties of those who were sick, but prevented them by His mercy.”

2. That He might sharpen the man’s attention to the instantaneous character of the miracle, and so to the words and deeds of Christ. From all these He might know with certainty that he was healed, not by the pool, nor by medicine, but by Christ alone, who was superior to all the virtue of the pool, or of medicine, and so might believe in Him as a prophet, and the Messiah, and might in penitence ask and obtain of Him remission of his sins. Wherefore He healed him beside the healing pool, but without touching it, that He might show that it was He who had given its virtue to the pool, and that He therefore, without the aid of the pool, could heal him by His word alone.

[7] Respondit ei languidus : Domine, hominem non habeo, ut, cum turbata fuerit aqua, mittat me in piscinam : dum venio enim ego, alius ante me descendit.

The infirm man answered him: Sir, I have no man, when the water is troubled, to put me into the pond. For whilst I am coming, another goeth down before me.

The sick man answered, &c. The sick man does not answer Christ’s question directly. He takes for granted that every one knew that he desired to be healed. Therefore he makes mention of the way of obtaining healing by means of the pool. As though he had said, “I am prevented by palsy from going into the pool, for I have none to carry me. I am a poor man. If therefore Thou canst help me in this matter, do so.” For he thought that when Christ asked the question, Dost thou wish to be healed? He meant, “Dost thou wish that I should carry thee into the pool, when the angel moves the water, that thou mayest in it be healed?” As yet he did not know the power of Jesus, for he had never seen Him.

The Syriac translates a little differently: Even so, Lord (I do wish to be healed), but I have not a man. Beautifully does S. Augustine say, “In very deed was that man (Jesus) necessary for his salvation, but it was that man who is also God.”

[8] Dicit ei Jesus : Surge, tolle grabatum tuum et ambula.

Jesus saith to him: Arise, take up thy bed, and walk.

Jesus saith unto him, &c. These words of Christ were practical and efficacious. In saying Arise, He caused him to arise, and healed him. As S. Augustine says, “It was not a command of work, but an operation of healing.” And S. Cyril, “Such power and virtue were not of man; it is a property of God alone to command like this.” Christ bade him take up his bed, that it might be evident to all that He had healed him, yea, that he had been made instantly stout and strong, so as to be able to carry his bed. Wherefore Euthymius in this passage observes that Christ was accustomed, after the miracles which He wrought, to add something by which their truth and greatness might be perceived. Thus in this instance He bade the paralytic take up his bed, which he could not have done unless he was healed; yea, stout and strong. So after the multiplication of the loaves, He ordered more fragments to be taken up than were originally in the bread. So He said to the leper whom He healed, “Go show thyself to the priest.” So He ordered something to be given to eat to the girl whom He raised from the dead (Mark 5:43).

Tropologically, S. Gregory (Hom. 12 in Ezech.) applies these words to sinners who have been justified by penance, who, by the just judgment of God, suffer temptations from their former sins. He says, “The sick man restored to health is bidden to carry the bed in which he had been carried. For it is necessary that every one who is healed should bear the contumely of the flesh, in which he had before lain in his sickness. What then is it to say, Take up thy bed, and go unto thine house, but, “Bear the temptations of the flesh; in which thou hast hitherto lain?”

Thus S. Mary of Egypt for seventeen years after her conversion suffered dreadful temptations of the flesh, because she had previously lived for that number of years immodestly. Sins therefore are their own executioners, and their own righteous avengers. What before pleased afterwards torments: what willingly thou hast done, the same thou shalt hereafter unwillingly suffer.

Symbolically, S. Augustine says (Tract. 17), “Arise; that is, love God, who is above. Take up thy bed; i.e., love thy neighbour, bear his infirmities, according to the words, ‘Bear one another’s burdens, and so fulfil the law of Christ.’ When thou wast weak thy neighbour carried thee: thou art made whole, carry now thy neighbour. Carry him with whom thou walkest, that thou mayest come to Him with whom thou desirest to abide.”

And immediately the man was made whole: and he took up his bed, and walked. And it was the sabbath that day.

And immediately (Syriac) in that moment … for on that day was the Sabbath. Christ designedly healed upon the Sabbath, both because the Sabbath was the highest festival of the Jews, which therefore it was right to sanctify above other days by good works, such as healing a sick man like this paralytic: and also because He hereby wished to show the Jews that He was the Lord of the Sabbath. For in bidding him take up his bed, which was a thing forbidden by the old Law, He showed that He was Messiah and God. Moreover, because the Sabbath was a day dedicated to rest and the praise of God, Christ gave rest from his pains to this sick man, and so afforded a notable occasion for praising God on this day.

The Jews therefore said to him that was healed: It is the sabbath; it is not lawful for thee to take up thy bed.

The Jews therefore, &c. As Nonnus paraphrases, “Clamorously they uttered an accusing charge, ‘It is the Sabbath, which every one ought to keep wholly in rest: it is not lawful for thee to carry thy bed.’ ” Speaking generally, they say the truth; for among the Jews it was a matter of the highest obligation to keep the Sabbath. All work was then forbidden, as appears from Exodus 20:8. And especially the carrying of burdens on that day is forbidden by Jeremiah (17:21, &c.). Christ, however, here says the contrary to the sick man whom He cured, because He, being Lord of the Sabbath, could dispense with its obligation. Moreover, what was forbidden by the Law upon the Sabbath was servile work, not a pious and Divine work like this. Christ bade the man who was healed take up his bed that the crowds of people who were flocking into the Temple on the Sabbath might become acquainted with the miracle, and acknowledge Jesus, its author, to be the Messiah, giving Him thanks.

[11] Respondit eis : Qui me sanum fecit, ille mihi dixit : Tolle grabatum tuum et ambula.

He answered them: He that made me whole, he said to me, Take up thy bed, and walk.

He answered them, &c. Understand, This was indeed a Divine man, and by Divine power has healed me. Therefore He is a friend of God, and would not bid me do anything except what is pleasing to God. As S. Augustine says, “Should I not receive a command from Him from whom I have received healing?” Just indeed was this defence of the sick man, which the Jews ought to have understood and accepted, but being blinded by pride they could not receive it, and so sinned by persecuting Christ and fell into hell.

[12] Interrogaverunt ergo eum : Quis est ille homo qui dixit tibi : Tolle grabatum tuum et ambula?

They asked him therefore: Who is that man who said to thee, Take up thy bed, and walk?

Therefore they asked him, &c. Being indignant, they say with threats, “Who is that bold and insolent man, who dare bid thee, contrary to the Law, carry thy bed upon the Sabbath day? Verily, that man is not of God who does not keep the Sabbath which God has ordained.” Thus they spoke through a blind prejudice derived from this Law, which they did not understand. Whereas, on the contrary, they ought to have understood that He who had miraculously healed the sick man, could not have done it except by the singular authority and help of God, and therefore that He had equally received from God the right to say on the Sabbath, Take up thy bed and walk.

[13] Is autem qui sanus fuerat effectus, nesciebat quis esset. Jesus enim declinavit a turba constituta in loco.

But he who was healed, knew not who it was; for Jesus went aside from the multitude standing in the place.

But he who was healed, &c. The man knew not the name of Jesus, nor whither He had gone, nor indeed who He was, for he had never seen Him before.

Departed. Euthymius gives the reason. “As soon as He had healed the man, He withdrew because of the crowd, partly to avoid the praise of the just, and partly to take away occasion for the envy of the unjust.” S. Chrysostom gives another reason: That the man’s testimony in the absence of Jesus might be less liable to suspicion. For if he who was healed had praised Christ to the Jews before His face, he might have seemed to have done it out of favour. But now that he praised Him in His absence, it is evident that he did so from the love of the truth.

[14] Postea invenit eum Jesus in templo, et dixit illi : Ecce sanus factus es; jam noli peccare, ne deterius tibi aliquid contingat.

Afterwards, Jesus findeth him in the temple, and saith to him: Behold thou art made whole: sin no more, lest some worse thing happen to thee.

Afterwards Jesus, &c. The Arabic is, Now thou art healed, return not to sin, lest a worse evil be done thee.

In the Temple. From this it appears that this man who was healed by Christ, as soon as he had carried his bed to his house, went to the Temple to give God thanks for His great benefit of healing. As Chrysostom says, “Assuredly a great mark of piety and reverence. He did not go to the market-place, or the porch; he did not indulge in pleasure, or ease; he was occupied in the Temple.”

Sin no more. From hence it is plain that God often sends diseases upon sick persons on account of their sins; and that this man had been afflicted because of his sins. Thus this paralytic, who had been sick for thirty-eight years, from a time before Christ was born, had committed some crime, which God wished him to suffer for, and expiate, by this protracted disease. Christ therefore tacitly admonishes the man’s conscience that he should be mindful of his sin, and be contrite, and avoid it for the time to come. At the same time He intimates that He, being a Prophet, knew this by Divine revelation. Wherefore when sickness is sent by God upon any one, let him examine his conscience, and blot out by repentance and confession the sin for which God has sent the sickness, and let him pray to God to pardon his sin, and take away the disease.

I said, often sends, for God sometimes sends diseases upon holy men that he may prove, increase, and crown their patience, as He did in the case of Job, whose whole dispute with his friends turned upon this point; his friends urging that his sins had given occasion to his being so grievously afflicted, whilst he, on the contrary, contended that he was free from sins, and had not deserved those afflictions. And God in the last chapter adjudges the dispute in his favour, and condemns his friends. The same thing will appear in the case of the man who was born blind (chap. 9), of whom Christ spake thus, “Neither did this man sin, nor his parents, that he was born blind.”

Moreover, as Christ healed this sick man’s body at the pool, so did He both by His inward inspiration, and by his external admonition, heal his soul in the Temple. He brought back to his memory the sins of his youth, by reason of which he had deserved so long a sickness, and he moved his heart to contrition for them, and to ask pardon from God, that so he might be justified. Indeed, Christ healed his body for this very reason that He might heal his soul.

Lest a worse thing, &c. “For,” as Theophylact says, “he who is not made better by a former punishment is kept for greater torments, as being insensate, and a despiser.” “And this happens,” says Euthymius, “either in this life, or in the life to come, or in both.” “A relapse is worse than the original disease.” So a relapse into a fault is worse than the fault on account of the greater ingratitude, boldness, impudence.

[15] Abiit ille homo, et nuntiavit Judaeis quia Jesus esset, qui fecit eum sanum.

The man went his way, and told the Jews, that it was Jesus who had made him whole.

The man went away, and told, &c. Not out of malevolence, but from gratitude, that he might not hide the author of so great a kindness. So Augustine, Chrysostom, and others. “He went away and told,” says Euthymius, “not as being wicked, that he might betray, but as being grateful, to disclose who was his benefactor. Because he thought he should be guilty of a crime if he kept silence, therefore he proclaimed the benefit.”

Totus tuus ego sum

Et omnia mea tua sunt;

Tecum semper tutus sum:

Ad Jesum per Mariam

No comments:

Post a Comment