St Luke Chapter XVIII : Verses 18-30

Contents

- Luke xviii. Verses 18-30. Douay-Rheims (Challoner) text & Latin text (Vulgate)

- Douay-Rheims 1582 text

- Annotations based on the Great Commentary

Luke xviii. Verses 18-30.

|

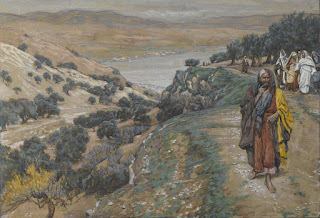

| He having heard these things, became sorrowful; for he was very rich. J-J Tissot. Brooklyn Museum. |

Et interrogavit eum quidam princeps, dicens : Magister bone, quid faciens vitam æternam possidebo?

19 And Jesus said to him: Why dost thou call me good? None is good but God alone.

Dixit autem ei Jesus : Quid me dicis bonum? nemo bonus nisi solus Deus.

20 Thou knowest the commandments: Thou shalt not kill: Thou shalt not commit adultery: Thou shalt not steal: Thou shalt not bear false witness: Honour thy father and mother.

Mandata nosti : non occides; non mœchaberis; non furtum facies; non falsum testimonium dices; honora patrem tuum et matrem.

21 Who said: All these things have I kept from my youth.

Qui ait : Hæc omnia custodivi a juventute mea.

22 Which when Jesus had heard, he said to him: Yet one thing is wanting to thee: sell all whatever thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come, follow me.

Quo audito, Jesus ait ei : Adhuc unum tibi deest : omnia quæcumque habes vende, et da pauperibus, et habebis thesaurum in cælo : et veni, sequere me.

23 He having heard these things, became sorrowful; for he was very rich.

His ille auditis, contristatus est : quia dives erat valde.

24 And Jesus seeing him become sorrowful, said: How hardly shall they that have riches enter into the kingdom of God.

Videns autem Jesus illum tristem factum, dixit : Quam difficile, qui pecunias habent, in regnum Dei intrabunt!

25 For it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.

facilius est enim camelum per foramen acus transire quam divitem intrare in regnum Dei.

26 And they that heard it, said: Who then can be saved?

Et dixerunt qui audiebant : Et quis potest salvus fieri?

27 He said to them: The things that are impossible with men, are possible with God.

Ait illis : Quæ impossibilia sunt apud homines, possibilia sunt apud Deum.

28 Then Peter said: Behold, we have left all things, and have followed thee.

Ait autem Petrus : Ecce nos dimisimus omnia et secuti sumus te.

29 Who said to them: Amen, I say to you, there is no man that hath left house, or parents, or brethren, or wife, or children, for the kingdom of God's sake,

Qui dixit eis : Amen dico vobis, nemo est qui reliquit domum, aut parentes, aut fratres, aut uxorem, aut filios propter regnum Dei,

30 Who shall not receive much more in this present time, and in the world to come life everlasting.

et non recipiat multo plura in hoc tempore, et in sæculo venturo vitam æternam.

Douay-Rheims : 1582 text

18. And a certaine Prince aſked him, saying: Good Maiſter, by doing what, ſhal I poſſeſſe euerlaſting life?

19. And IESVS ſaid to him: Why doeſt thou cal me good? None is good but only God.

20. Thou knoweſt the commandements: Thou ſhalt not kil, Thou shalt not commit aduouterie, Thou ſhalt not ſteale, Thou ſhalt not beare falſe witnes, Honour thy father & mother.

21. Who ſaid: Al theſe things haue I kept from my youth.

22. Which IESVS heaing, ſaid to him: Yet one thing thou lackeſt: Sel al that euer thou hast, & giue it to the poore, and thou ſhalt haue treaſure in Heauen: and come follow me.

23. He hearing theſe things, was ſtroken ſad: because he was very rich.

24. And IESVS ſeeing him ſtroken ſad, ſaid: How hardlu ſhal they that haue money enter into the Kingdom of God?

25. For it is eaſier for a camel to paſſe through the eye of a nedle, then for a rich man to enter into the Kingdom of God.

26. And they that heard, ſaid: And who can be ſaued?

27. He ſaid to them: The things that are impoſſible with men, are poſſible with God.

28. And Peter ſaid: Loe, we haue left al things, and haue followed thee.

29. Who ſaid to them: Amen I ſay to you, there is no man that hath left houſe, or parents, or brethren, or wife, or children of the Kingdom of God,

30. and ſhal not receiue much more in this time, and in the world to come life euerlasting.

Annotations

[The following Notes are adapted from the Great Commentary on Chapter xix of St Matthew's Gospel. The verse numbers are those of St Luke's Gospel]

18. And a certain ruler asked him, saying: Good master, what shall I do to possess everlasting life? S. Jerome thinks that this one was the lawyer of whom Luke speaks (x. 25), and so that he came with the intention of tempting Christ. S. Chrysostom’s opinion is preferable, that it was a different person, and that he came with a sincere intention of asking how he could become like a little child, according to Christ’s precept, and so become a partaker of everlasting life. Wherefore he is the same person who is spoken of in Luke xviii. 18. This becomes plain by a comparison of the two passages, especially ver. 22, where it is said that when he had heard Christ’s doctrine concerning perfection, If thou wilt be perfect go and sell what thou hast, and give to the poor, he went away sorrowful because he was rich. But this is evidence that he had asked these things of Christ from a sincere desire of salvation.

Good Master: This is a common Hebrew form of salutation by which persons sought the good will of a doctor or prophet. As though they said, “Rabbi, I know that thou art good, both as a man, and as a doctor and a prophet, who teachest us those things which are indeed good, and which lead to happiness. Tell me therefore what special good thing shall I do, that I may obtain the chief good in Heaven?” He plays upon the word good.

19. And Jesus said to him: Why dost thou call me good? The Vulgate translator read in the Greek, τί με ἐρωτᾷς περὶ ἀγαθοῦ; This was S. Augustine’s reading, and that which S. Jerome followed in his commentary. Why askest thou me concerning good? The present reading is that given in the text. Origen gives both readings. He subjoins the reason, saying—

None is good but God alone. viz., in His nature and essence. Humbly does Christ refer this praise of His goodness to God, that He may teach us to do the same. For this man had not perfect faith concerning Christ, nor did he believe Him to be God. To this faith Christ desired to raise him by chiding him as it were. As though He had said, “If thou callest Me good, believe that I am God: for no one is good of himself save God.” So S. Jerome, Theophylact, Euthymius.

Moreover good means the same as perfect, and the perfection of a thing is its goodness. That God is perfect, S. Denis proves in many ways (de Divin. Nomin. c. 10.) In God there is infinite perfection both of nature and wisdom, of power, holiness and virtue. There is therefore in Him the highest goodness, natural, moral and supernatural. Wherefore He is the Fountain of all good, in whom all the excellencies of all creatures are gathered together, and infinitely more than there are in the creatures. Wherefore in God there is in an eminent degree the beauty of gold, the splendour of jewels, the savour of delicacies, the harmony of music, the pleasantness of gardens, and whatsoever there is lovely, pleasant and delicious in the creatures. Hence it is from God that honey derives its sweetness, the sun its radiance, the stars their light, the heavens their glory, angels their wisdom, men their virtue, animals their sensations, plants their life, and all other things whatsoever they have of good: yea it is to the bounty of God that they as mendicants owe their very existence, as a drop out of the ocean. In God therefore is all good, and that in a perfect and infinite degree. In God is the allurement of all love, the consummation of all desire, the satisfying of all appetite. Why then, O wretched man, dost thou wander about among these poor created goods, and with all art not satisfied? Seek good in Him in whom is all good. Love and desire God. He alone can fully satisfy thy appetite and thy thirst: in this life through grace, but bow much more in the life to come through glory: yea by Himself. For in heaven God manifests Himself that He may be beheld by the blessed as the chief good, that they may taste Him and enjoy Him.

20. Thou knowest the commandments &c. Christ in this place only propounded the precepts of the second table having reference to our neighbour, because in them are included the precepts of the first table concerning God. For the love of God produces love of our neighbour. For we love him for the sake of God. Wherefore the love of our neighbour flows from love of God. Again it is more difficult to love our neighbour than to love God. For who is there who does not love God, especially among religious people, such as this youth was?

21. Who said: All these things have I kept from my youth. From my youth; Syriac and Arabic, from my childhood—meaning, from a child I have been brought up in God’s law, and been prevented by His grace. I have carefully kept all God’s commandments. What lack I yet? i.e., of goodness; that I may become perfected therein, and have eternal life? Not in any fashion, as all have it who keep the commandments, but surely and securely, and in large measure; in the chief and perfect degree of happiness and glory. For Thou, O Christ, as the Master of Heavenly virtue seemest to deliver a higher doctrine concerning it than our Scribes. Tell me therefore what it is? For I covet salvation and perfection. R. Jerome thinks that this young man told a falsehood, for if he had loved his neighbour as himself, he would have sold all his goods, and given to the poor. But this argument is not absolutely convincing. For to love one’s neighbour as oneself is of precept: but to give all one’s goods to the poor is of counsel. And Christ, as Mark says, beholding him, loved him, and gave him this advice concerning bestowing all his goods upon the poor, that he might go on to perfection.

22. Which when Jesus had heard, he said to him: Yet one thing is wanting to thee &c. This is not an evangelical precept, but a counsel. Whence He saith, if thou wilt. This is to say, I do not command, but I advise. Mark adds (x. 21), Then Jesus beholding him, loved him, and said unto him, One thing thou lackest: go thy way, sell whatsoever thou hast, and give to the poor. S. Anthony, hearing these words of Christ read at Mass, left all things, and so followed Christ, says S. Athanasius in his life. S. Prosper of Regium, who was afterwards a bishop, did the same, in the time of S. Leo, as is recorded in his Life in Surius. June. 25.

Deservedly therefore S. Bernard says (in Dedaman. sub initium.), “These are the words which in all the world have persuaded men to a contempt of the world, and to voluntary poverty. They are the words which fill the cloisters with monks, the deserts with anchorites. These, I say, are the words which spoil Egypt, and strip it of the best of its goods. This is the living and effectual word, converting souls, by the happy emulations of sanctity, and the faithful promise of truth. For Simon Peter saith unto Jesus—Lo we have left all things.” Wherefore S. Jerome, by this saying of Christ, as by the sound of a trumpet constantly stirs up his own people, as well as all of us to a zeal for poverty. Whence (Epist. 150, ad Hedib.), he says, “Dost thou wish to be perfect, and to stand in the first rank of dignity? Then do what the Apostles did. Sell what thou hast, and give to the poor, and follow the Saviour; and follow the bare and only cross with virtue for thine only cloke.” Still more clearly does the same S. Jerome speak (Epist. 24, ad Julian.), “And this I exhort, if thou wilt be perfect, if thou desirest the summit of Apostolic dignity, if to raise up the cross and follow Christ, if to take hold of the plough, and not to look back, if placed on the top of the house, thou despisest thine old garments, and wouldest escape the Egyptian woman, thy mistress, leaving the world’s pallium. Whence also Elias, when he was hastening to the kingdom of Heaven is not able to go with his mantle, but leaves his unclean garments to the world (mundo immunda vestimenta dimittit.). But this, thou sayest is a question of Apostolic dignity, and of the man who wishes to be perfect. But why art thou unwilling to be perfect too? Why shouldest not thou who art first in the world, be first also in the family of Christ?” After a little he adds, “But if thou shalt give thyself to the Lord, and being perfect in Apostolic virtue, shalt begin to follow the Saviour, thou shalt then understand where thou art, and how in Christ’s army thou holdest the last place.”

Observe: Christian perfection chiefly and primarily consists in charity; nevertheless it is placed by Christ in evangelical counsel as it were means and instruments suitable for acquiring charity. (See S. Thomas, ii. 2 q. 184, art. 3.) This perfection all the religious aim at who renounce all their possessions, that naked they may follow a naked Christ. Yet do not all immediately at the beginning obtain this perfection, but they tend towards it by degrees; and by making continual progress, they at length arrive at it. Hence, wisely does Climacus (Gradus 26) make three grades of such persons—namely, beginners, those who are making progress, and the perfect. To beginners he delivers this alphabet, not of twenty-four letters, but of virtues. “The best elementary alphabet of all,” he says, “is obedience, fasting, a hair shirt, ashes, tears, confession, silence, humility, vigils, fortitude, cold, fatigue, affliction, contempt, contrition, forgetfulness of injuries, brotherly love, gentleness, a simple and incurious faith, the neglect of the world, the affections kept free from all things, simplicity united with innocence, voluntary vileness.” To such as are making progress he assigns these greater precepts of virtues. “The lot and the method of those who are progressing is victory over vain glory and anger, a good hope of salvation, quietness of mind, discretion, a firm and constant remembrance of the Last Judgment, mercy, hospitality, modest reproof, speech free from all vicious affections.” Lastly, to the perfect he delivers these maxims of complete sanctity: “A heart free from all captivity, perfect love, a fount of humility, the mind’s departure from the vanities of the world, and going to Christ, a treasure of light and Divine prayer secure from robbers, abundance of divine illumination, desire of death, hatred of life, and flight from the body.” And then he adds that “a perfect man is so holy, and so pleasing to God, that he may be the ambassador, or the patron and advocate of the world, who is able (in a certain sense) to compel God; the colleague of angels, and is with them initiated into mysteries; a most profound depth of knowledge, a habitation of celestial mysteries, a keeper of the Divine arcana, the health of men, a god over devils, a master of vices, an emperor of the body.”

sell all whatever thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come, follow me. You will ask, Why is poverty the appropriate way and instrument of evangelical perfection? Bonaventura answers (in Apol. Paupcrum), because cupidity is the root of all evils. Cupidity, therefore, is the foundation of the city of Babylon. For of it are born ambition, gluttony, and the rest of the vices. This cupidity Christ cuts down by poverty, and takes away riches, honours, delights, which are the food and fuel of all vices. For delicacies make the mind effeminate, and to become women rather than men. A manly strength abhors delicacies. 2. Poverty begets humility, which is the foundation of sanctity. Whence S. Francis, says Bonaventura, being asked by his disciples what virtue would most commend us to Christ the Lord, and make us pleasing to Him, replied (according to his wont): Poverty; for it is the way of salvation, the fount of humility, the root of perfection, and from it there spring many fruits, although they be hidden and known to but few. 3. One who is poor in spirit, since he has no other cares, gives himself wholly up to gathering virtues, as a bee to gathering honey. Thus S. Anthony, being free from the desire of riches, had an insatiable desire of virtues; and so from one man he learned patience, from another abstinence, from another constancy, prayer, and so on. Hence the first poor religious were called Ascetics, that is, exercisers; because they were wholly occupied in taming anger, gluttony and other passions, and in the practice of arduous and heroic virtues. Whence some of them were accustomed to take food only once in two days, others only once in three. Others scarcely slept at all, like those who lived in the monastery of the Acemetœ—i.e., of those who keep vigil without sleeping. 4. Because perfection consists in the love of God and our neighbour; and to this poverty directs us. For it puts an end to meum and tuum, from whence all the strifes and wars arise among neighbours, says S. Chrysostom. The same removes the mind away from all care and love of earthly things, and fixes it wholly upon God. For what the Apostle says concerning a married man (1 Cor. vii. 33), applies also to a rich man: “He that is married cares for the things of the world, how he may please his wife,” and is divided. For the rich man is divided. He divides his cares and his thoughts between God and Mammon. Poverty, therefore, makes a man superior to the world and the flesh, like an angel conversing with angels, breathing after Heaven. And such a one fulfils the words of the Apostle, “Seek those things which are above, not the things that are upon the earth,” that he may place his whole mind and love upon God, and may be made with Him, as it were, one spirit. Perfection, therefore, consisteth in this—that the mind be altogether abstracted from transitory things, and fixed on what is good and eternal; that is, on God, for which poverty affords an opportunity.

You will say, for this it is sufficient to leave all things in affection, which was what Abraham did, not in act. I answer with S. Jerome against Vigilantius. That is one grade of poverty, and a lower one. For the highest is to relinquish all things in reality, both because such a one gives all, that is to say both intention and its effect, as also because it is not possible wholly to relinquish a thing in intention, without carrying the intention into effect. For like a person lying in a bed, or sitting in a chair, if any one should secretly bind him to the chair he does not know that he is bound, until he gets up: so those who possess riches have their affection hidden, by which they are bound to them, and do not perceive it until they lose them or leave them. Thus S. Gregory records (Epist. ante lib. Moral.) how he was deceived by the world. “There was opened to me even then that I should seek for the eternal love, but persistent habit had prevailed so that I should not change my outward life.”

sell all whatever thou hast, and give to the poor, From hence the Pelagians taught that no rich man can be saved, unless he sell his property, and give to the poor, and become poor himself. S. Augustine writes against this view (Epist. 89. ad Hilar.), teaching that this is a counsel not a precept. Whence Pelagius was compelled to retract this error of his, as S. Augustine testifies (Epist. ad Paulin.).

sell all whatever thou hast, and give to the poor. Mark and Luke add, all things whatsoever thou hast. By these words is refuted the error of Vigilantius and Calvin, who teach that it is better and more perfect to keep one’s riches, and use them in moderation, and give to the poor according as opportunity serves, than to relinquish them all at once. S. Jerome confutes this error, (lib. cont. Vigilant.). For as S. Ambrose says, “It is better to give the tree with its fruit than to give the fruit only.” Again, the ascetic, who gives part of his wealth to the poor, and keeps part for himself, is neither fish nor flesh: he neither renounces the world, nor is he a secular. He is a sort of amphibious animal. Whence S. Basil said to one who took up the religious life, but reserved certain things for himself, “Thou hast spoilt a senator, and not made a monk.” Such a person does not wholly trust in God, but partly in God, and partly in the riches which he keeps for himself. Whence he is not really and entirely poor in spirit, nor does he free himself from the care, distraction and temptation, which are wont to accompany riches. Wherefore S. Anthony commanded a certain person who wished to renounce the world after this sort, that he might reserve something for himself against a time of necessity, to place upon his naked body some pieces of flesh which he had bought. When he had done this, the dogs and birds, which came to snatch at the flesh, lacerated his body all over. Then S. Anthony said, “Thus shall they who do not renounce all things be torn by the devils.” (See Rufinus, in the Lives of the Fathers, lib. 3, n. 68.) Wherefore S. Hilarion, as S. Jerome testifies in his Life, rejected money offered him to distribute among the poor by Orion, out of whom he had cast a legion of devils, and said, “To many the name of poverty is an occasion of covetousness: but mercy has no art. No one spends better than he who reserves nothing for himself.” For as S. Leo wisely says about a like matter (Serm. 12, de Quadrages.), “Through lawful use we pass on to immoderate excess, when from care of the health there creeps in the delectation of pleasure; and the desire of what is sufficient for nature does not satisfy.” S. Gregory gives the reason d priori (Hom. 20, in Ezech.), “When any one vows something that is his to God, and something does not vow, that is called sacrifice. But when a man vows all that he has, all that he lives, all that he knows, to Almighty God, then it is a holocaust. For there are some who as yet are retained in mind in this world, and who afford help to the poor from their possessions, and hasten to succour the oppressed. These in the good which they do, offer sacrifices, because of their actions they offer something to God, and keep something for themselves. And there are some who reserve nothing for themselves, but immolate senses, life, tongue, and the substance which they have received to Almighty God. What do these do but offer a holocaust, yea rather are made a holocaust?”

and give to the poor. Christ does not say, Give to your relations, or rich friends, as Remigius observes. For this is an act of natural love, by which you do not cast away your riches, but deliver them to those who belong to you, to be kept. Wherefore in this way you do not leave the world, but rather immerse yourself further in it. You must make an exception, when your relations according to their position are in need of your riches; for then, they are reckoned poor in their own station. But give to the poor, from whom you expect nothing in return, but from God only. Therefore this is a pure act of charity and poverty, and renunciation of wealth. Origen adds, he who gives his goods to the poor is assisted by their prayers.

thou shalt have treasure in heaven. By the word treasure, says Chrysostom, “the abundance and the permanence of the recompense are shown.” And S. Hilary says, “By the casting away of earthly riches heavenly wealth is purchased.” Beautifully does S. Augustine observe (Serm. 28, de Verb. Apost.), “Great is the happiness of Christians, to whom it is given, to make poverty the price of the kingdom of Heaven. Let not thy poverty displease thee. Nothing richer can be found than it is. Would you know how wealthy it is? It purchases Heaven. By what treasures could be conferred what we see granted to poverty? That a rich man should come to the kingdom of Heaven with his possessions may not be: but he may get there by despising them.” Sell clay therefore, and buy Heaven: give a penny and procure a treasure.

and come, follow me Journeying in poverty, and preaching the kingdom of God. “For many,” says S. Jerome, “even when they leave their riches do not follow the Lord. Neither does this suffice for perfection, unless after despising riches, they follow the Saviour; that is, leave evil and do good. For the world is more easily set at nought than the will. Therefore do the words follow, and come, follow me. Again, Follow Me implies the union of an active with a contemplative life.

There is a threefold sort of holy life. The first and lowest is the active life. The second is the contemplative. The third and most perfect is the union of action with contemplation, that what we derive from God by contemplation, we should afterwards teach to others.

This was the life which Christ and His Apostles led. S. Ambrose gives the reason in his explanation of the title of the 39th Psalm. “Christ,” he says, “is the end of all things, which with a pious mind, we ask for. For whether you seek for wisdom, or study virtue, or truth, or the way of justice, or the resurrection, in all things you must follow Christ, who is the Power and the Wisdom of God: who is Truth, the Way, Justice, Resurrection. After whom therefore do you strive, but the perfection of all things, and the sum of virtues? And therefore He saith to thee, Come, follow Me, i.e., that thou mayest deserve to arrive at the consummation of virtues. Therefore he who follows Christ ought to imitate Him as closely as he can; to meditate upon His precepts, and the Divine examples of His deeds.”

23. He having heard these things, became sorrowful; for he was very rich. Wisely says S. Augustine (Epist. 43. ad Paulin.), “I know not how it is that when superfluous earthly things are loved, the more acquired the more they bind. Wherefore did that young man depart in sorrow, except because he had great riches? For it is one thing to be unwilling to incorporate with yourself what you have not; it is another thing to tear away what has been incorporated. The former may be repudiated as something not belonging to you: divesting yourself of the latter is like cutting off your limbs.” In the Gospel according to the Hebrews which Origen cites, there is here a considerable addition. It is as follows. “Another of the rich men said unto Him, Master, what good thing shall I do that I may live? He saith unto him, Man, keep the Law and the Prophets. He answered Him, I have done this. He said unto him, Go and sell all that thou possessest and divide amongst the poor, and come, follow Me. But the rich man began to scratch his head, and it pleased him not. And the Lord said unto him, How sayest thou, I have kept the Law and the Prophets? For it is written in the Law, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself, and lo, many of thy brethren, the sons of Abraham, are clothed in filthy garments, and perish of hunger, and thy house is full of many good things, and there goeth not out of it anything whatsoever unto them. And He turned and said unto His disciple Simon, who was silting by Him,—Simon, son of Jonah, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of Heaven.”

25. For it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God. The Arabic is, the entering of a camel into a needle’s eye is more easy. And again, the Gr. πάλιν δὲ, i.e., but again. Christ, in giving this addition, as it were corrects what he has just said: “I have said that it is a difficult thing for a rich man to be saved, now I add something more, that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter Heaven.” By rich man, Remigius understands one who trusts in riches, who places all his hope in them, which is what many rich men do. More simply you may take it to mean any rich person.

You will ask, What is the meaning of camel in this passage, and how could it pass through a needle’s eye? Some, with Theophylact, understand in Greek a sailor’s cable, which is κάμηλος, a camel. Some, with the Gloss, understand a gate of Jerusalem; which, because it was very low, was called the camel, because it was necessary for him who entered through it to stoop down and bend like a camel.

But I say that the tall and hump-backed animal, which is commonly called a camel, is here meant. So the Syriac, Arabic, Origen, SS. Hilary, Jerome, Chrysostom, and others, passim. Whence note that it was a proverb among the Jews, when they wished to signify that a thing was impossible, to say, “A camel will more easily pass through a needle’s eye, than such a thing will be.” Whence the Talmudists use such a proverb even now, as Caninius testifies (in nom. Hebr. N. Test.). Similar proverbs, signifying that a thing is impossible, are the following: “More easily will a tortoise outstrip a hare.” “A wolf might take a sheep to wife first.” “A locust will bring forth an ox sooner.” “A tortoise will vanquish an eagle.” “The earth will take to itself wings.” “Rivers will run uphill.” “More easily might you hide an elephant under your arm.” “You will fly without wings first.” “A beetle will more readily make honey.” “The sky will fall first.” “The sea will more easily produce vines.” “Words will be wanting to a woman sooner.” “More easily may you feed on wind.”

Moreover, there is an hyperbole here. That is called impossible which is exceedingly difficult. Whence, that a rich man should be saved, which Christ here says is impossible, in the verse preceding He said was difficult. As S. Jerome observes, “Not impossibility is declared, but infrequency is shown.” So too Jansen, Maldonatus, and others. Thus, in the twelfth verse, He said, He that is able to receive it, let him receive it. It means, some cannot receive, i.e., with difficulty receive the counsel of celibacy. And Jeremiah says (xiii. 23): “If the Ethiopian can change his skin, or the leopard his spots, so too may ye do good when ye have learnt evil.” (Vulg.) And yet this might be done, though it would be difficult. So it is as impossible—that is to say, difficult—for a rich man to be saved, as it would be for a camel to go through the eye of a needle. And yet, speaking absolutely, such a thing could take place: if, for example, the camel were cut up into the minutest particles, each one of which was passed separately, though slowly and laboriously, through the needle’s eye. Or if some needle were made great and thick, that it should be like a tower or a pyramid; for then its eye would be of sufficient size for a camel to pass through it whole. Lastly, Emanuel Sa, by the eye of a needle, understands what a needle has, or what a needle does, for it is possible to make with it by degrees an immense aperture.

Again, you may take impossible here in a strict sense. For that a rich man should be saved is impossible with men: but it is possible with God, as Christ says in verse 26. That is to say, it is impossible by natural strength, but by the power of the grace given by God it is possible. Just as that a camel should pass through the eye of a needle is possible by the power of God. That this is possible with God is plain from a similar case; namely from the quantity of the body of Christ, which in the Eucharist is wholly contained in a very small Host, yea in every particle of it. For if God is able to place the whole body of Christ in a Particle of a consecrated Host, He is able also to make a camel pass through the eye of a needle.

Appositely and elegantly says Francis Lucas, a rich man puffed up and swelling with his riches, on whose back great burdens of wealth are pressing is compared to a camel, and the strait gate, by which we must enter into life to the eye of a needle, that you may understand that those who abound in riches, and are swelling with pride and disdain in too great a degree to allow themselves to be reduced within those narrow bounds in which God confines His own people are meant. I have given many analogies between a camel and a rich man in Ecclus. xiii. 11.

By this similitude of a camel and a needle Christ signifies that his riches are not so much an advantage to a rich man, as an impediment to virtue, and the kingdom of heaven. Wisely therefore did He counsel the young man that he should give his wealth to the poor, and as a poor man follow Christ who was poor.

Mystically. Isaiah prophesied that camels, i.e., rich men, laying aside by the grace of Christ the hump of their pride, would enter into the Church through the eye of a needle, i.e., through the straits of humility and the evangelical law (lx. 6). “The company of camels shall cover thee, the dromedaries of Midian and Epha.” Hear S. Jerome, “Such was thy mother Paula of saintly memory, and thy brother, Pammachias, who through the eye of a needle, that is by the strait and narrow way which leadeth unto life, passed, and with their burdens leaving the broad way, which leads to Tartarus, carried whatever they had as the Lord’s gifts, according to the saying, “the ransom of a man are his riches,” for the things which are impossible with men are possible with God.”

Allegorically, S. Augustine (lib. 2, quæst. cap. 47), and S. Gregory’ (lib. 35, Moral. 17), by camel understood Christ and by the needle, His Passion. Thus, it is more easy that Christ should suffer for lovers of the world, than for lovers of the world to be converted unto Christ. Hear S. Gregory, “A camel passed through the eye of a needle when our Redeemer entered through the straitness of His Passion, even unto the enduring of death. This Passion was like a needle, because it pricked His body with pain. But more easily could a camel pass through the eye of a needle than a rich man enter into the kingdom of heaven, because unless He had first shown unto us by His Passion the pattern of humility, by no means would our proud rigidity have bowed down.”

Symbolically and Anagogically, Auctor Imperf. (apud. S. Chrysostom Hom. 33) says, “The souls of the Gentiles are likened unto crooked camels, in which was the hump of idolatry, because the knowledge of God is the lifting up of the soul. But the needle is the Son of God, of which the first part is subtle according to the Divinity: but the rest is thicker according to the Incarnation. But the whole is straight, and hath no bending, through the wound of whose Passion the Gentiles entered into life. With this needle the garment of immortality hath been sewed. It is the very needle which has sewed the flesh to the spirit. This needle hath united the people of the Jews to the Gentiles. This needle hath brought about friendship between angels and men. It is easier then for the Gentiles to pass through the eye of the needle than for the rich Jews to enter into the kingdom of Heaven.”

26. And they that heard it, said: Who then can be saved? Because there were few, and at that time scarcely any, who did not wish to be rich. For all were gasping after lucre, even as many gasp after it now. For as S. Augustine says upon this passage, “All who desire riches are counted among the rich.”

28. Then Peter said: Behold, we have left all things, and have followed thee. Our ships and our nets, by which we gained our livelihood. And although these were poor and small things, yet, as S. Gregory says (Hom. 5, in Evang.), “he has forsaken much, who has left the desire of having. By those who followed Christ as many things were left as could be desired by those who followed him not.” For the poor in spirit, although he may be reckoned among the needy, yet in a sense is he rich, because all the things which he might have, hope for, or obtain, all his lifelong in the world, yea, the whole world, he forsakes for the love of Christ, that he may give up his whole heart to God. This is an heroic act of poverty, and therefore of charity and religion in which a man offers himself as a whole burnt offering to God: yea he himself becomes a living and perpetual burnt offering.

Hear S. Augustine. (In Psalm ciii., Conc. 3.) “Peter left not only what he had, but what he wished to have. For what poor person is there who is not puffed up by worldly hopes? Who does not daily desire to increase his possessions? That cupidity was cut off. Peter left the whole world, and Peter received the whole world. ‘Having nothing, and yet possessing all things.’ ”

+ + +

SUB tuum præsidium confugimus, Sancta Dei Genitrix. Nostras deprecationes ne despicias in necessitatibus, sed a periculis cunctis libera nos semper, Virgo gloriosa et benedicta. Amen.

The Vladimirskaya Icon. >12th century.

Totus tuus ego sum

Et omnia mea tua sunt;

Tecum semper tutus sum:

Ad Jesum per Mariam.

No comments:

Post a Comment